Bushtit

Bushtit

BY DAVE ZITTIN

Bushtits rarely show up in our backyard, but we have seen them a few times over the years. Bushtits are social. They live in flocks of 10 to 40 individuals. When it’s cold, they huddle at night to keep warm. They feed as a flock, gleaning insects and spiders from trees. When one decides to move to another tree, the others follow in an irregular single file line. They take on every imaginable position when feeding, frequently hanging upside down, much like Chestnut-backed Chickadees.

Bushtit by Dave Zittin

Bushtits make a lot of noise, but it can be difficult to hear their ethereal calls on windy days. Their incessant calling keeps the group in touch with each other. The calls are low in volume and are high-pitched squeaky “tsips” and “pits”. To my ears, they sometimes sound like small crystals making a faint tinkling sound as if they are a living wind chime.

Bushtits are the only members of the family Aegithalidae, the long-tailed tits, in North America. The family has 4 genera and 11 species and most occur in Eurasia.

Bushtit by Treasa Hovorka

Bushtits have an unusual, well-camouflaged nest. It resembles a tube sock, about 1 foot in length, and hangs from live or dead branches. There is a hole near the top that allows entry into a narrow tube that widens near the base of the sock-like nest. The nest construction is constructed from vegetative matter, animal hair, and spider webs which give a nest a stretchy quality. It is well insulated and allows the parents to leave the young alone for longer periods than if the nest were open to the elements.

Bushtit and nestling in nest by Janna Pauser.

Bushtits are one of the first birds to be described as having nest helpers. Helpers are not the biological parents but will help the parents build a nest and later help feed the young. Evolutionists study species with helpers to promote understanding of the selective advantages that come to a non-parent in helping a mating pair to raise young. Observation shows that most Bushtit helpers are unmated males or males that have lost a nest. Helpers are not common among west coast Bushtit, but field research has shown almost 40% of active nests in the Chiricahua Mountains of Southeast Arizona have helpers.

Attracting Bushtits to Backyards

Bushtits are not attracted to feeders. They are foliage-gleaners and consume small arthropods found on leaves, petioles, and branches. A brushy or treed yard is the best way to attract Bushtits.

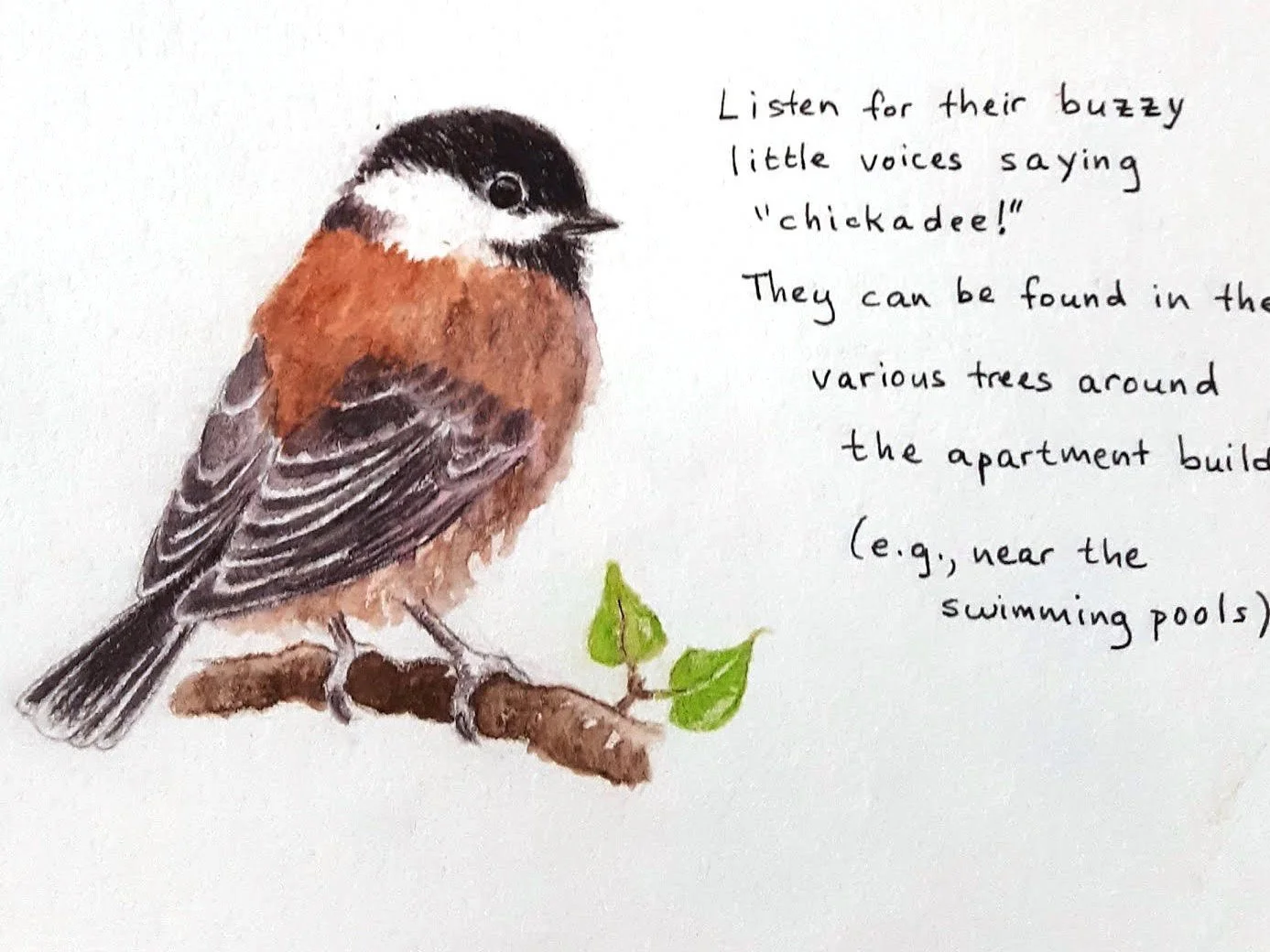

Description

Bushtits are small, mostly gray birds about the size of a Ruby-crowned Kinglet (3-4 inches in length). They have a large head, a rounded body, and a long tail. The beak is small and pointed. The sex of an adult is determined by the color of its iris. Females have irises which are a dull yellow to milky white color. Males have dark irises. Young Bushtits of both sexes have dark eyes. Bushtits in the Pacific region have upper parts that have a brownish wash; those in the interior have white upper parts.

Female Bushtit by Dave Zittin. Note the whitish eyes, rounded head, short beak and long tail.

Male Bushtit by Teresa Cheng. Note the dark iris.

Distribution

Bushtits are found in the western U.S. Their northern limit is in southern British Columbia, and they extend south into Central America. They are not known to migrate long distances, but are constantly in foraging mode, moving from tree to tree searching for food. They do come down from high-altitude areas to avoid the winter cold and during this time they may be found in brushy desert areas.

Similar Species

Nothing looks like a Bushtit in Santa Clara County. In the dry southwest, the young Verdin resembles a Bushtit, but their bills and other features are different. The uniform gray color of the Bushtit, its social nature, and chickadee-like behavior make for easy identification in Santa Clara County.

Explore

More Backyard Bird Information

View more common Santa Clara County Backyard Birds

Visit our Backyard Birding page

Tell us what you’re seeing in your yard! Send your notes, photos, and sound clips to backyardbirds@scvas.org. We’ll feature your submittals on our website.

Banner Photo: Bushtit by Vivek Khanzodé